Then to B Bus we all switch

But mixing using cheesy wipes

Gets Propel in such a stitch!

Each of the three television studios in the Communication Building had an associated control room located nearby, usually a room next door that was viewable through a thick pane of glass. Student directors could see and communicate with the talent on the floor not only via the equipment but also by simply turning their head, looking through the glass, and sticking out his or her tongue. This action conveyed such a rich spectrum of emotion and was used more than it should have been. There were no rules in place to prevent such things from repeating.

The control room for Studio 3 was a respectably-sized room and probably could have had more going for it had it not been made into a junkyard. And really, not even a good junkyard – more like a walk-in closet that needed emptying. One corner of the room contained equipment for Studio 3; surely there was an audio board and maybe a cart machine, too, though neither had been top-of-the-line merchandise in years. Opposite this was even more archaic equipment but regulated to boxes or stacked vicariously in strangely-shaped piles that wobbled when someone stomped or sneezed or even spoke.

Between all of this was a towering contraption about three-feet-square, maybe five-or-six-feet tall, and on wheels. I laugh when mentioning the wheels as I vividly recall someone trying to move the monstrosity to retrieve a fallen paper and having no luck: the wheels were either jammed, worn down, or just for decoration. The reason didn’t matter. This was the video switcher.

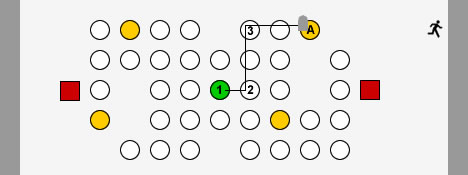

- The bus, essentially a row of buttons indicating various inputs (e.g. camera 1, camera 2, VTR [video tape recorder], etc.).

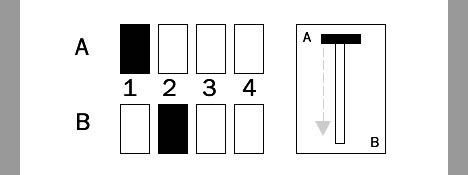

- The fader bar, what was used to create transitions between the two busses.

Cue talent.

In the simplest of mixers, whichever bus the fader is delegated to is active and directed toward the output source, or program monitor. On the switcher the A bus is active and the monitor shows Brad. Brad asks Rachel a question. The director instructs a switch to camera 2; this is done by the switcher operator moving the fader bar down to the B bus. Now the B bus is active; the monitor shows Rachel.

The transition between the two busses varied, as it could be a swap between the two inputs (i.e. a “cut” or “take”) or something a bit more elaborate, such as dissolves or fades or the dreaded wipes. Wipes came in numerous forms: star-shaped, heart-shaped, or iris-shaped, which was a growing or shrinking circle. In all the studios in the Communication Building, as well as in all the television production rooms, were graphics machines that enabled text, basic graphics, and a compendium of wipes.

Dr. Propel hated wipes to the point that he instructed to write down one of his cardinal rules: “Wipes are cheese.” Wipes were nothing more than cheesy effects that were overused and perpetuated by those incapable of original thought. Our wipes were pretty cheesy: there was a cow wipe (the image of a cow grew to fill the entire screen with the second input), the rolling dice wipe (two die are rolled from the center of the screen, grow larger, and the second input image is seen in the dot as the cube comes closer), and the mildly-popular Peeping Tom wipe (a woman walks by an open window, is shocked to see someone peeping in, and she pulls down the curtain that reveals the other input).

In short, wipes were as cheesy as some of Propel’s jokes and mannerisms. That, and the switcher was relatively easy to use.

Now we just had to take what we learned after using all the equipment and apply it to usage outside the classroom.

That meant the radio station. Fun times were just ahead.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Switch

(Engine Alley)

Engine Alley

From the album Engine Alley

1994

At the no go show you can stay all day

You won't know no no what to say

If it's a radio show it might be better that way

There's too many people with nothing to say

You can go, you can go

Radio show Radio show

You can go, you can go

I switch on the rayjo (at a quarter to 12)

And then I switch off the rayjo (at a quarter past 12)

When I switch on the rayjo switch! switch!

I have to switch off the rayjo

At the no go show you could stay all day

You didn't know no no what to say

It was a radio show and it was better that way

There's too many people with nothing to say

You can go, you can go

I switch on the rayjo (at a quarter to 12)

And then I switch off the rayjo (at a quarter past 12)

When I switch on the rayjo

And when I switch off the rayjo

Switch! Switch!

When I switch on the radjo

I have to switch off the radjo Ho Ho